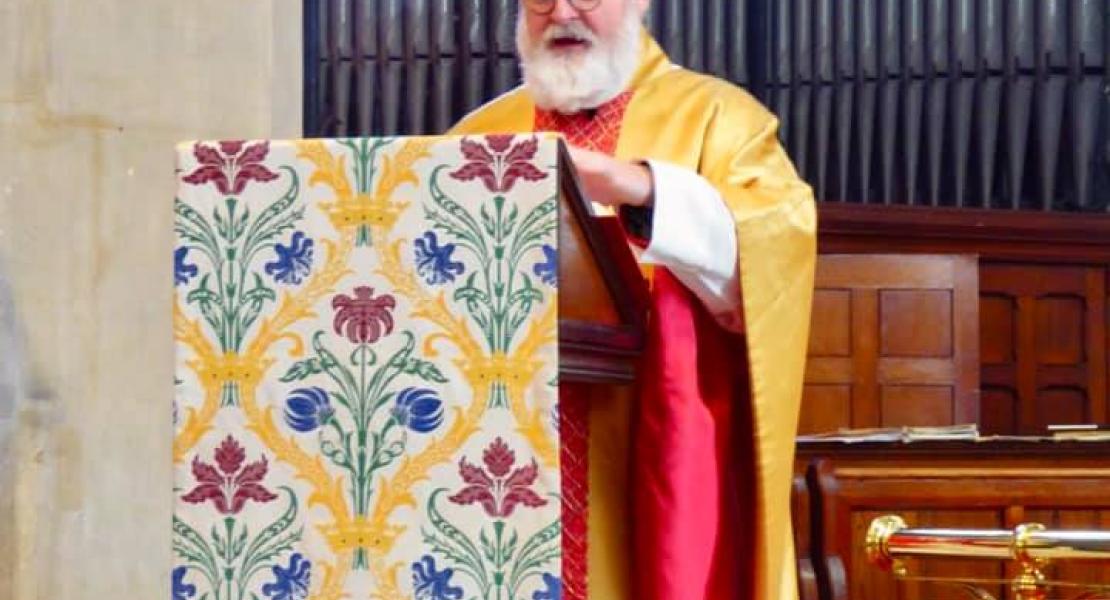

Visit of Bishop Jonathan - Sunday 9 May at the 10.30am Parish Mass when we celebrated the Feast of the Passion of St John the Evangelist, our patron saint.

I am delighted to be with you on this first celebration of your patronal feast in summer, and grateful too to be with Fr Brendan so soon after his appointment as your pastor.

Dear Friends, the Church is not holy by herself; in fact, she is made up of sinners. We all know it. It is plain for all to see! She is made holy, every day and night, by the Holy One of God, by the purifying love of Christ. And that is what this feast of the Beloved Disciple, St John, is about. But it's not only about him: it's also about you, and about me.

Various important Christian writers in the second and third centuries testify to the fact that St John died, at a very great age, at the close of the first century, nearly 70 years after the events of Jesus's death and resurrection. No one doubted these traditions. Some say he was as old as a hundred! He died at Ephesus (in modern Turkey) where it is said he wrote his gospel. And it is from one of these writers, an African called Tertullian (De praescript., xxxvi), that we also get the testimony that, during the reign of the Emperor Domitian (81-96) John was thrown into a cauldron of boiling oil in front of the Latin Gate, one of Rome's fortified southern gates, and that he emerged from the trial without suffering any injury. Unsurprisingly after such unexpected outcome, John was banished, to the Aegean island of Patmos, from which he returned to near-by Ephesus after Domitian's death, to live out his final few years.

Now, I suppose that since none of those details are in the Bible, we're free to take or leave the story, despite the fact that we regularly attribute much more astonishing things to God - like the Son of almighty God being born in human form. For nothing is impossible to Him who is the very source of all power and life. So let's think a bit deeper.

John was the last surviving apostle. Having lived so long in one of the most well connected of the early centres of Christianity, John will have heard reports come in, one by one, from across the empire, about the martyrdom of his fellow apostles and their closest collaborators. His own brother, James had been the first (Acts 12.1-2). There was no reason for John to suppose that, in the long run, he would be an exception. The persecutions of the Church would catch up with him too, eventually. Over his long life surely he would often have remembered Jesus's words to him and his brother James, which we heard in today's gospel, when their rather pushy mother asked Jesus for places of honour for her boys in the kingdom of God. 'Are you able to drink the cup that I am to drink?' replied Jesus. With no idea what they were talking about, 'We are', they said, 'You will', He said: 'oh! you will'. But only the Father can give you places in His kingdom. And so - like the story in the book of Daniel of the three young men who emerged unharmed from the Burning Fiery Furnace - the story of John's survival expresses an inescapable truth about the extraordinary collective witness of the Holy Apostles in the face of persecution. John met what was sure to be his own very grim martyrdom, and did not run away. He knew it was coming to him. He accepted it. Though God rescued him from it John made his sacrifice; he drank the cup that Christ drank, and for a few more years continued to serve the Church, exhorting persecuted Christians all over the empire to be steadfast in the faith and not to identify with the pagan world. He encouraged them to live the Death and Resurrection of Christ openly in order to make clear to the world the real meaning of human life and history.

2 All this makes us wonder how he would have approached the prospect of martyrdom and what we can learn from it. Surely we can recognize his mindset from his teaching in the new testament, and I want to draw out two aspects in particular.

First, the central content of John's Gospel and his Letters is the work of divine love, charity. John is the evangelist who stresses the unquenchable strength of love that caused the Father to send His Son into the world of men; and the unfathomable depth of love that motivated the Son's compassion for sinners, and His sacrifice for us all. 'The bread I will give, for the life of the world, is my flesh' (Jn 6.51) Jesus says. This God not only spoke, but He loved us, very realistically – loved us to the very limit of love's sacrifice, the death of His own Son. So John's first motive was divine love.

The second motive is his description of our response to that love. In his gospel he records Jesus saying to Nicodemus 'He who does the truth comes to the light' (3. 21). Each person who trusts the Lord, and does what He commands in His teaching, embracing any loss and suffering, draws ever closer and closer to the light that enlightens every person. In other words, it is our actions – not primarily our words – that reveal our grasp on Christ's truth and the extent of our enlightenment by love. Deeds come before doctrine; understanding of the Lord, will come to you only if you carry out faithfully and sincerely the commands and good deeds the Lord teaches.

3 'This is the love of God', John wrote in one of his letters to the churches, 'that we keep His commandments. And His commandments are not burdensome. Everyone who has been born of God overcomes the world.' (1 Jn 5.3 - 4). Several ancient writers mention that in his final years St John would constantly repeat Jesus's words 'Beloved, love one another'. Being transformed by the love of God, and being united with the love of God, will then always involve the fundamental offering of our obedience to Christ if, like our Lord, we are to win souls for Christ, even if that obedience were to involve a vat of boiling oil. We shall never avoid suffering. But here we come face to face with a central Christian paradox, according to which suffering is never the last word but rather, a transition towards happiness; indeed, suffering itself is already mysteriously mingled with the joy that flows from hope. It is the means of our transformation and unity with Christ's love.

So much of the suffering in our lives, and the lives of every other human being – our losses, our sacrifices – goes to waste. We should be offering it up obediently for God's glory. As a consequence we would come to the light all the sooner, while also saving others around us. If, like St John, we were willing to use our sufferings, to help us to offer ourselves more profoundly, and more completely, more trustfully to Christ – to be offered with Christ, and to be transformed by Him – then it is we ourselves who, like the bread and wine we offer, would be transubstantiated by Christ, transformed into service so that through us man could know how sweet is the love of Christ!